Community News

Japan's National Foundation Day on Feb. 11 marks national controversy

Yokota African American Heritage Association February 2, 2023

()

One day out of the year many Japanese nationalist groups and Shinto shrines throughout Japan celebrate a national holiday with parades and ceremonies, while the Japan Teachers Union and other groups assemble and rally in protest of the holiday.

That day is Kenkokukinen-no-Hi, or National Foundation Day, on Feb. 11. And its history and making are as complicated and controversial as the pastimes that now surround it.

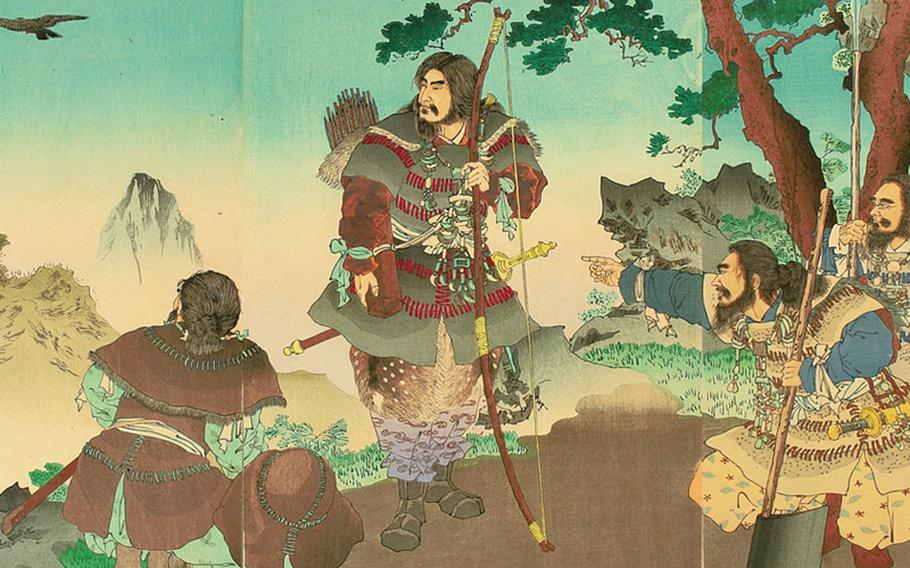

Although this government-established holiday is called “National Foundation” Day, unlike other holidays whose names imply the founding of a nation, such as Independence Day, there is no specific historical date tied to this one. It is based on the Shinto-inspired myth of when the first emperor, Jimmu, ascended the throne as divine ruler of the newly formed Japanese nation. Here in lies the controversy.

While to some it is a source of national and cultural pride, to others it is a throwback to an emperor system that has no factual base – one that facilitated the actions of Imperial Japan leading up to and during World War II.

“This national holiday was designated by a government ordinance to reflect on the establishment of the nation and nourish a love for the country,” a spokesperson of the National Cabinet Office’s holiday section said in 2015.

The government, however, has been careful to steer clear of the controversy.

“Definitions of the National Holidays Law suggest that each citizen may observe national holidays in accordance with each position and condition,” the spokesperson continued. “So, although private organizations run events to celebrate the holiday or express their objection to it, the government has never hosted any event relating to the holiday.”

So what’s the hoopla over National Foundation Day really about?

According to “The Chronicles of Japan” (“Nihon Shoki”), Japan’s first national history book, Emperor Jimmu was enthroned in A.D. 660 on what the Meiji government (1868-1912) later interpreted as Feb. 11, according to the solar calendar.

The Meiji government first celebrated it as national Empire Day in 1873. Today, it is widely understood by many Japanese that this was done – at least in part – as a way to legitimize and enforce its new rule by making the Meiji Emperor a divine descendent of Jimmu.

Leading up to and during World War II, this national holiday was celebrated with a great passion, pomp and circumstance. Large parades and festivals were held at the Imperial Palace and major Shinto shrines throughout Japan.

It was considered one of Japan’s four major holidays along with the birthdays of the previous Emperor Meiji and the then-current Emperor Showa and New Year’s. The Constitution of the Empire of Japan was decreed on this day in 1889; afterward, it was commemorated on Feb. 11 as well.

After the war, however, the Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers abolished the holiday. Ironically, or perhaps by design, Feb. 11, 1946 was the day Gen. Douglas MacArthur approved the draft version of Japan’s new postwar constitution.

As soon as the Occupation ended in 1952, legislators began lobbying to reinstate Empire Day. After much debate, nine bills, countless amendments and even a public survey, 14 years later it was reinstated as National Foundation Day in 1966.

Though stripped of most of its overt references to the emperor, because of its history, the controversy surrounding National Foundation Day still remains.

“This national holiday was originally celebrated as Empire Day since the beginning of Meiji era,” the spokesperson said. “Although it was eliminated for a couple of decades after World War II, it has been continuously celebrated among Japanese as a tradition.”